The following article was published on Livewire Markets on 22 June 2021.

Over the last few months, the most common question we have been asked is, “what’s your view on inflation?”

Google Trends shows we are not alone; in May, worldwide interest in searches on “inflation” doubled from 2020 levels and was the highest since 2009. Similarly searches on “transitory” doubled in May reaching the highest level since 2005.

So, like everyone else in the investment community we thought this month there was only one topic worth discussing: inflation. And in order to reflect both sides of the debate, we’ve decided to allow you to be a fly on the wall for a debate between myself, Pete Robinson, and a senior portfolio manager in the liquid credit team, Michael Bors.

Kicking things off, we asked: Where do you see inflation over the next few months?

Pete Robinson: I feel like it is clearly going higher over the next few months and the key point here is that I don’t think it is just a catch up from last year but it will overshoot, and possibly by a lot.

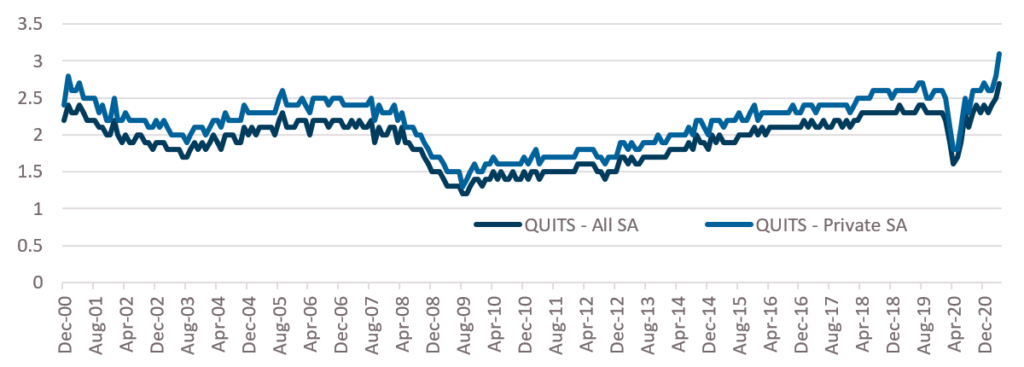

One data point that I have been focused on is the QUITS rate in the United States. For April the private sector QUITS rate hit a high of 3.1%, the highest level dating back to 2001, when the series first began.

US JOLTS QUITS Rates

Quit rates are an important forward-looking inflation indicator because when someone quits their job, the new hire generally earns a higher wage than the quitter (Bank of America put this figure at 13%). Add to this the supply chain pressures that are leading to price increases across all parts of the economy whether it is used car prices, chip shortages, timber prices, or textiles. In the United States, spending on goods is up around US$1 trillion over pre-COVID levels. Sure, spending on services is lower but only by around US$0.5 trillion and it is catching up fast as the global economy reopens.

Domestically, I think the pressures are likely to be even stronger given how much our labour markets rely on overseas workers. We talk about this a lot but remember that in Australia over the coming years there is projected to be over 1 million fewer people in the country than were projected pre-COVID. Whether it is backpackers to pick the fruit and vegetables, chefs to work in our restaurants, or even auditors, significant labour force pressures exist across the wider economy. As evidence, job vacancies in Australia are 50-60,000 above pre-COVID levels and at the highest levels on record.

Michael Bors: So sure, US inflation has now printed a high level for two consecutive months and that seems like that is the path of least resistance in the short term. COVID has been a massive shock met with wartime like fiscal and monetary stimulus but are we really in a new regime that changes the path of the last two decades?

It is a big call to suggest the major disinflationary themes of the pre-COVID era (debt, demographics, and disruption), can be overcome by policy makers running settings hotter for longer than normal.

The multitude of COVID handouts has been great for recipients to bridge themselves to the other side. MMT proponents would suggest that it can continue forever, but again there must be some appreciation the Government largess will eventually moderate and thus will act as a cap on peak inflation expectations.

With big variations in health factors and the vaccination rollout, the reopening phase was always going to be lumpy and contain some anomalies such as the unsustainable skew of consumption towards goods versus services.

Huge pent-up demand from bored consumers and disrupted supply chains combined with base effects need to be thought of in the context there is still material labour market slack. In the USA, U6 unemployment is still above 10% and as a reminder, there wasn’t any meaningful inflation in the pre-COVID era when the U3 unemployment rate was under 4% for the 18-month period prior to COVID.

In places like Australia, where the headline unemployment rate is now very near the pre-COVID level and some employers are facing select labour shortages, the RBA’s business liaison program suggests that such firms are responding with an array of levers other than raising wages.

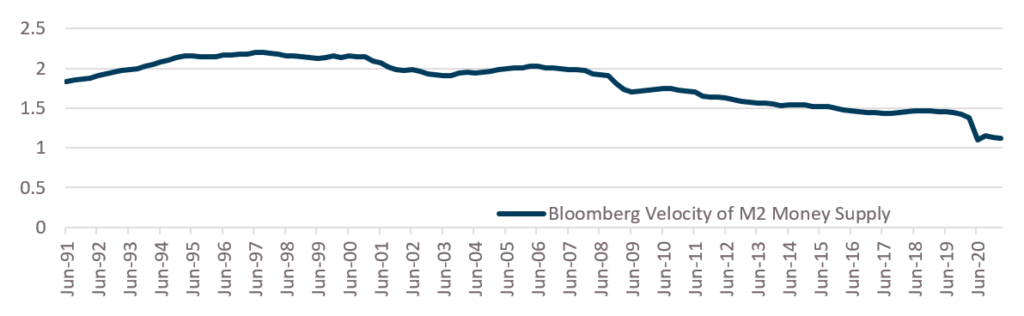

The “monetarists” among us might be excited by the surge in money supply but they can’t ignore that the velocity of money still looks structurally impaired. With a much-improved vaccine rollout in many parts of the developed world, we are a little bit closer every day to a more tangible reopening that will help soothe some of the pressures like labour mobility.

I acknowledge evidence of supply chain disruptions is still abundant, but equally, I wouldn’t want to write off the profit motive of suppliers to respond by increasing capacity or simply experiencing less disruption as the initial post-opening surge in demand wanes.

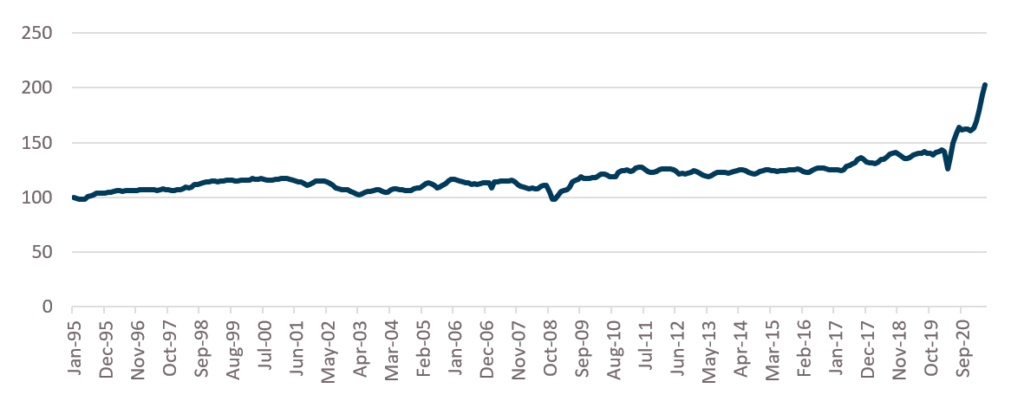

As commodity traders like to say, the best cure for high prices is high prices. The auto sector, where the surge in used car prices has made an outsized contribution to headline US inflation, is going to be an ideal place to watch this play out.

Bloomberg Velocity of M2 Money Supply

Robinson: Yep, I agree on a lot of this, particularly your points around longer-term deflationary themes but as Keynes said in the long run we are all dead. I actually think the challenge here is identifying when the tide of short-term impulses gets overwhelmed by these longer-term trends. This comes down to this whole question around what “transitory” actually means.

There seems to be this belief that there will be a couple of months of wage increases, some cost inflation and then we will be done with inflation and return to normal programming. I just don’t think it works that way.

Inflation is all about expectations; the expectation of inflation begets inflation and it can occur with significant lags. I see you get a wage increase, I expect to get one myself. You see me get a pay rise and you expect one.

And many of these supply chain pressures are going to take many months, even years to be reversed.

- When are we getting international students back in Australia at pre-COVID numbers?

- When are vaccination rates in developing economies going to match those in the developed world?

These aren’t questions for Q3, 2021 but are questions for 2022 or even 2023. Add to this the fiscal response which, as you say is being withdrawn, but slowly and carefully. Fiscal policy is still expansionary and will remain so for some time during which the inflationary animal spirits will continue to build.

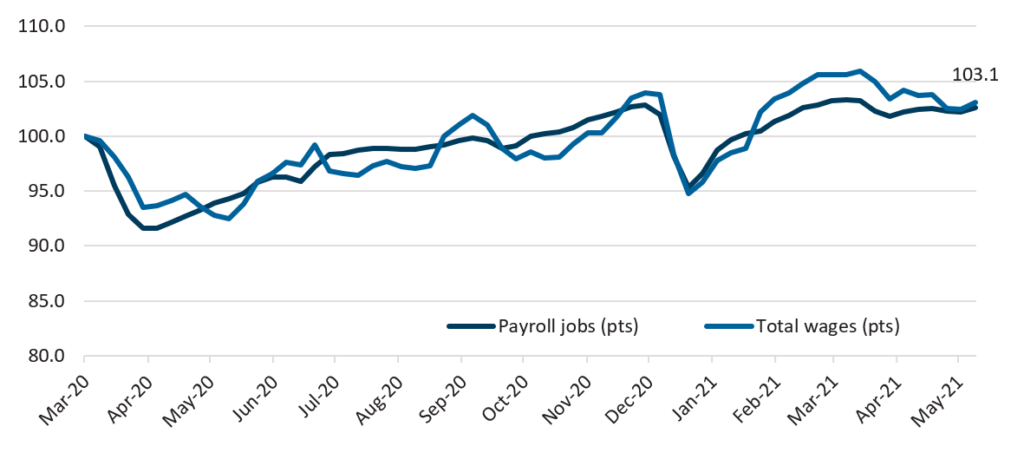

As for unemployment, I fully acknowledge that while total wages are above pre-COVID levels, unemployment rates remain elevated and at least in the United States, there are still many more people out of a job than was the case pre-COVID. But in Australia, there are more people in jobs now than pre-COVID (13.04 million in April 2021 versus 12.97 million in December 2019) and we have all-time high job vacancy levels. Yes, JobKeeper was a factor in keeping people employed but the ending of that program seems to have only had a marginal impact as the weekly payrolls data shows (see below).

Payrolls jobs and total wages, indexed to the week ending 14 March, 2020

The big challenge here is not predicting inflation. It sounds like at least in the near term we think it will be elevated. It’s the policy response that is difficult to predict.

Do you think there is a chance that a few months of inflation running hot will force central bankers hands here?

Bors: Let’s agree to disagree about some of these topics. Perhaps an easier topic to agree on is how remarkable it would be if markets managed to transition out of this period of extraordinary intervention and policy settings without experiencing an episode of illiquidity or volatility.

A more sustained inflation spike could easily be that catalyst, particularly if the labour market tightness you cite above actually translates into stronger headline payrolls data at the same time.

Central bankers sound authoritative and strongly committed to expansionary settings, but as we all know, their forecasting track record is far from perfect. When we are talking about a potential change to a long-term trend like falling inflation, the forecasting job isn’t going to be easy to get right, and even more difficult to get right for the correct reasons. They are also suitably nervous about the potential for an inadvertent tightening of financial conditions given the experiences from tapering in 2013 and 2018.

Similarly, policymakers know each of their own actions has important ramifications for their peers and in turn back to themselves. Perhaps this a reason to err on the side of expecting patience and a preparedness to look through higher inflation prints in the coming months.

We are now seemingly back to a situation when even the most minute changes in communication are at the forefront of rates markets. If however, patience is the order of the day, then what does the lagged policy response look like? Does it need to be even more aggressive than if had occurred earlier? In the meantime, I need to write an advertisement to sell my once nice but now high mileage, heavily worn, used car for an absurd price while I still can.

Manheim US Used Vehicle Value Index

Robinson: I think in a roundabout way we are getting to a similar place. What matters here is the policy response and the steel of policymakers to stay the course if they believe that inflation is going to be transitory.

Because as you say, the longer they leave it, the more aggressive the response will need to be IF they are wrong. And IF they are wrong and inflation proves to be more sticky than they had anticipated, I agree it is almost unthinkable that policymakers could unwind these extraordinary positions without some extreme illiquidity and volatility.

JPMorgan has already discussed the link between positive inflation surprises and the positive bond-equity correlation. Think of what happens if that persists – there is approximately US$1 trillion in risk-parity strategies tied to this relationship. What happens if the Fed is tapering at the same time risk parity strategies are losing assets under management? I guess the answer is the markets aggressively sell-off and the Fed is forced to halt tapering and intervene to stabilise markets. Again.

Coming out of this, the key question for investors is what assets will perform if and when equities and bonds are both selling off. Where do you hide? We think short-dated credit is a pretty good place and we’ll delve into this more in a future piece.

On that cheerful note, we might wrap it up here so I can go and get a COVID jab and Michael, it sounds like you need to sell a car!

Unless otherwise specified, any information contained in this material is current as at date of publication and is provided by Challenger Investment Partners Limited (CIP Asset Management, CIPAM) (ABN 29 092 382 842, AFSL 234678), the investment manager of the CIPAM Credit Income Fund ARSN 620 882 055 (Fund). Fidante Partners Limited ABN 94 002 835 592, AFSL 234668 (Fidante) is the responsible entity and issuer of interests in the Fund. Fidante and CIPAM are members of the Challenger Limited group of companies (Challenger Group). Information is intended to be general only and not financial product advice and has been prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider whether the information is suitable to your circumstances. The Fund’s Target Market Determination and Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) available at www.fidante.com.au should be considered before making a decision about whether to buy or hold units in the Fund. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Fidante and CIPAM are not authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADI) for the purpose of the Banking Act 1959 (Cth), and their obligations do not represent deposits or liabilities of an ADI in the Challenger Group (Challenger ADI) and no Challenger ADI provides a guarantee or otherwise provides assurance in respect of the obligations of Fidante and CIPAM. Investments in the Fund are subject to investment risk, including possible delays in repayment and loss of income or principal invested. Accordingly, the performance, the repayment of capital or any particular rate of return on your investments are not guaranteed by any member of the Challenger Group.