This article featured in Livewire, 25 February 2022.

Last week we were surprised to read comments from Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey suggesting that workers should not demand pay rises, lest they create a wage price spiral and drive higher inflation. His comments provoked significant outcry and not unjustifiably so as he had not been so vociferous in demanding businesses not increase prices in response to supply chain pressures and labour shortages.

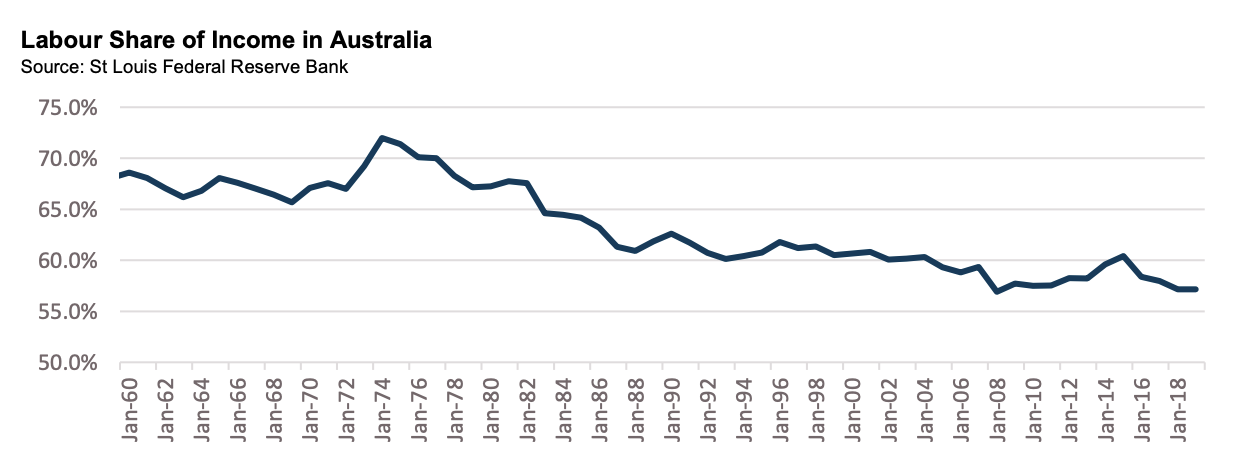

The comments also led to us returning to a topic we have been ruminating over for some time. That is the balance of power between labour and capital. Looking backwards, the balance has clearly moved towards capital. In Australia (below) and most of the developed world, labour has contributed a decreasing share of income over the past 50 years.

Astute readers will notice that the charts end in 2019, before the COVID pandemic begun so the obvious question is whether COVID has impacted these trends. Historically, the labour share of income initially increases in a recession as growth slows, before declining as businesses cut back on costs.

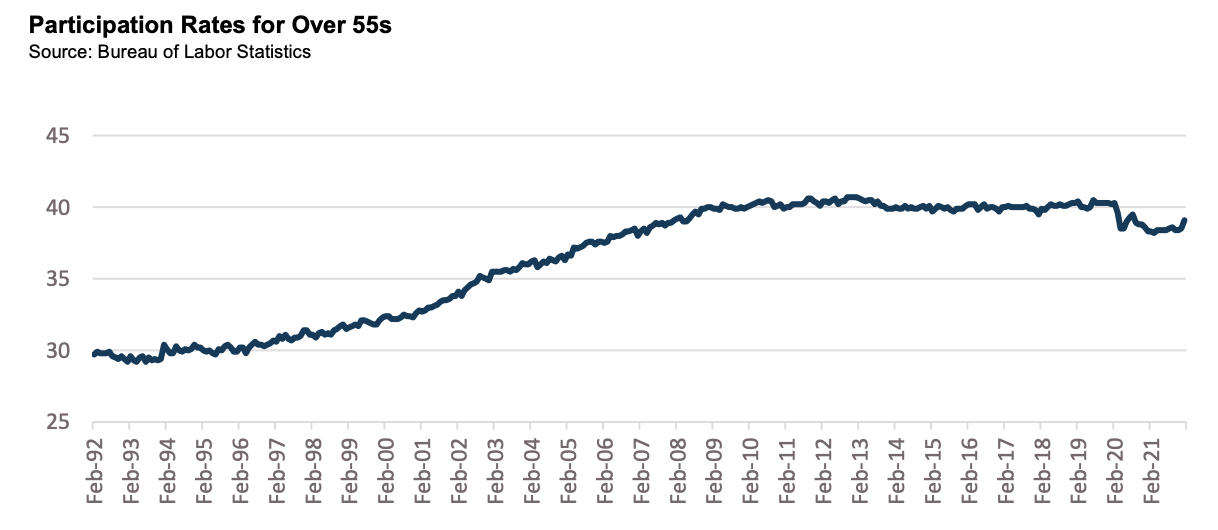

However, in developed economies, there are signs that this may not be occurring in the same way it has in the past. Transfer payments from the government have been significant meaning many people have simply not returned to the labour market despite significant demand for labour. Demographics may have played a role here too as Baby Boomers don’t look like they need to come back to the labour force and net inward migration has slowed due to border closures.

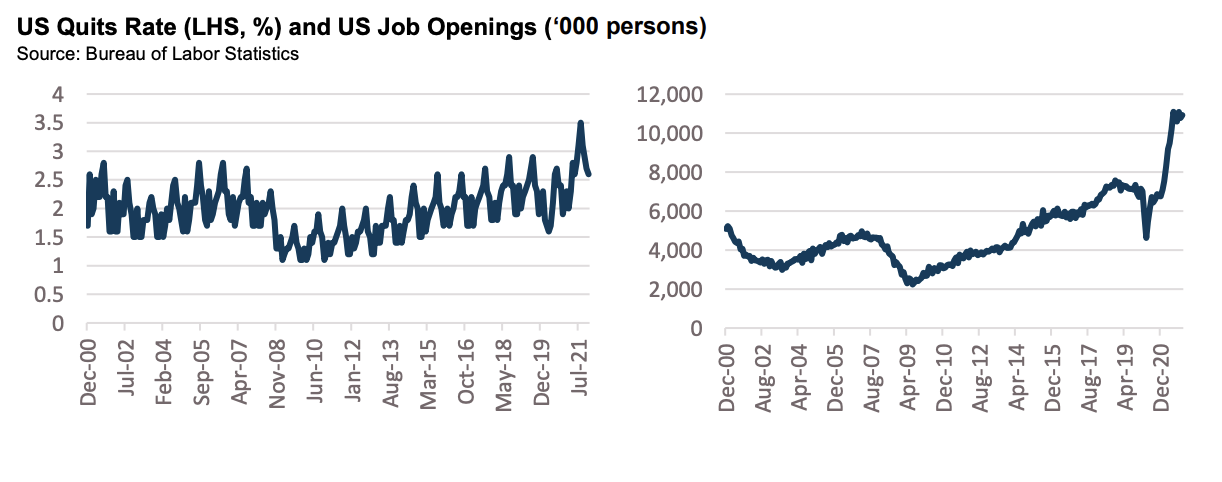

The below charts show quit rates and job openings, both of which are elevated well above pre-COVID levels. It looks like the mistake central bankers made was to assume everyone who was part of the labour force pre-COVID would return. They haven’t. Over COVID, job openings have increased by 4 million. People are quitting at a rate that is 20% higher than pre-COVID levels and the average rate from 2004 to 2006 when the cash rate increased from 1% to over 5%.

To place these numbers in context, the difference between 2019 quit rates and 2021 quit rates is circa 7 million more people voluntarily leaving their job every year.

When someone leaves their job voluntarily, there is typically a pay rise associated with the move so increasing quit rates feed through directly to inflation. Labour force participation rates tell a similar story. They have declined for the past two decades, having peaked in the late 90s. What is notable, is that recent declines have been concentrated in over 55-year-olds. These are likely permanent reductions in the labour force.

Right now, labour has a stronger bargaining position than it has had for decades. The major question for markets is whether this is a cyclical or structural trend.

The declines over the past 50 years were certainly structural and attributable to a multitude of factors including demographics (individuals staying in the workforce longer and net inward migration to developed economies), social norms (increased female participation rates), industrial relations (reduction in the influence of unions) and of course, increased debt levels (ability to borrow to increase the return on capital investment).

We think a reversal in those trends would have a strong inflationary impulse. Today US 5 year forward inflation swaps are pricing at 2.4% per annum suggesting the near term inflation we are currently experiencing will not persist for the medium term.

The long end of the interest rate curve seems well anchored.

The tail risk event investors need to prepare for is that near term inflation persists into the medium term leading to a repricing in the long end of the interest rate curve.

This piece was authored by Pete Robinson, Head of Investment Strategy and Portfolio Manager, CIP Asset Management.