The structure and valuations of fixed income markets have changed dramatically over the past decade or so. Most obviously, interest rates have decreased dramatically and the compensation for taking traditional forms of fixed income risk have declined in tandem. Some of these changes may unwind as we enter a world of higher inflation and withdrawal of central bank stimulus measures over the coming years, but other changes are much more structural in nature.

In particular, regulations requiring banks to hold more capital are likely to persist, with an enduring impact being a withdrawal of banks from competing in certain types of lending and reducing their balance sheet commitments to liquidity provision in public credit markets during times of stress. This is creating both challenges and opportunities for asset managers and their investors as alternative sources of credit provision whilst navigating a disrupted liquidity environment and low returns for their traditional liquid bond portfolios.

As such, institutional and retail investors have been forced to adjust their approach to fixed income because of these changing dynamics, with the embrace of private debt markets alongside exposure to traditional public credit allocations in an effort to boost returns. Private debt is a complex asset class that can offer a differentiated opportunity set with unique return, risk, liquidity, and diversification benefits.

Part 1 of this paper will explore the issues above and, while Part 2 will examine how co-mingling public and private credit in a single portfolio can offer a solution to many of these issues and may offer one of the best opportunities to maximise the potential of each.

Distinguishing between public and private debt

Private credit is often also referred to as “direct lending” or “private lending” or even “alternative credit.” Irrespective of the name, they are basically loans to borrowers originated directly by a non-bank asset manager rather than via an intermediary.

Unlike traditional bond issues or even syndicated loans (such as US term and leveraged loans), there is little intermediation between borrower and lender. The lender basically arranges the loan to hold it, rather than originating to sell it. As such, the borrower and the lender have a much closer and more transparent relationship, directly negotiating the terms of the finance.

In a recent Economist magazine special report on the asset management industry, one of their concluding forecasts was that private debt would become an increasingly important asset class. As the Economist notes,

“The growth of private debt is, in large part, a response to the retreat of banks from lending to midsized businesses and their private-equity sponsors. Asset managers, starved of yield in the government-bond markets, are happy to fill the void.” (1)

Private debt is now a significant subset of broader credit markets globally. Underlying exposures include private loans to mid-size or non-listed corporates (often backed by private equity sponsors), commercial, industrial and residential real estate loans that sit outside the risk appetite of the banking sector, as well as loans secured by securitised assets such as mortgages, other loan receivables (particularly from non-bank lenders) or ‘alternative’ cashflow streams such as royalty streams, insurance premiums or solar panel lease payments.

A key distinction—and advantage—across many types of private debt is the ability to customise lending terms thus exercise greater control over credit risk protection compared to public markets. Private credit investors can influence or dictate elements such as coupon and principal payment schedule (amortisation), loan covenants, information access and control rights, tailoring investments to their desired liquidity, return and credit risk profile.

In addition, this customisation does not come at the expense of returns. By not introducing an intermediary to arrange the transaction, the fees otherwise paid to the arranger can be shared between borrower and lender, enhancing the overall return profile of the investment relative to syndicated transactions.

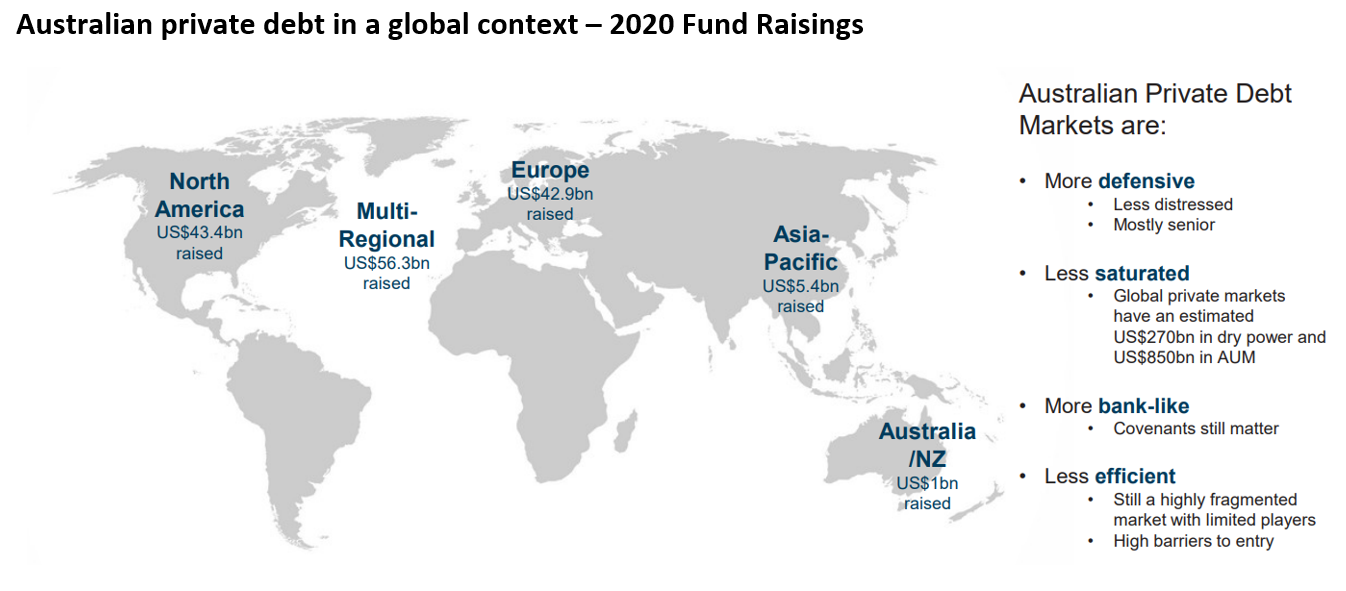

Australia remains a relatively nascent market compared to offshore growth in private debt assets and corporate credit generally. But this comes with significant advantages due to the lack of competition from asset managers bidding down yields and credit protections to obtain deal flow means that underwriting standards and margins remain strong.

Sources: Private debt investor, Prequin, CIPAM Estimates

What is the Illiquidity premium and why does it exist?

Any risk premium in investing can be thought of as a transfer of economic rents from risk avoiders to risk takers. In equities, for example, there is a strong, academically established risk premium for investing in small cap companies. This is theorised to exist because these stocks often have less liquidity stemming from their lower overall market capitalisations and lower free float for external shareholders as well as less diversified revenue streams and/or robust balance sheets.

In many respects, similar arguments can be made for the existence of a higher rate of return expectation for private debt over public credit.

The simplistic explanation is that private debt arrangements do not have the consistent structural features of public credit that facilitate consistent and efficient investor evaluation, such as official credit ratings, combined with security identifiers and legal structures that enable centralised clearing and settlement and thus easy trading.

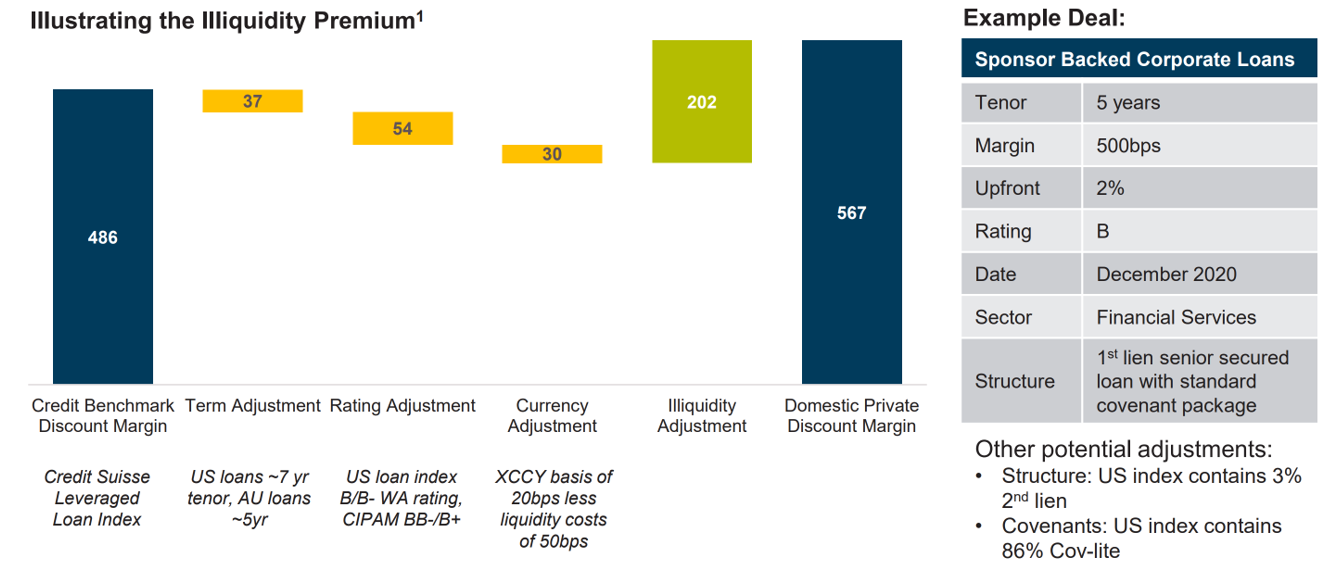

This means that borrowers who obtain financing from such sources must pay a higher interest rate for a given level of implied credit risk to lenders, who need that higher rate of return to justify their reduced flexibility in managing their investment. Thus, by comparing the rate paid between private debt and public debt at the same assumed credit rating or risk level, one can establish a proxy for the quantum of the illiquidity premium.

Term Adjustment based on difference between 5 and 3 year discount margins for Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan index. Rating Adjustment based on difference between the Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan index. Currency Adjustment based on the short term rolling cross currency basis of 10 basis points less the cost of holding 10% in liquids at a cost of 4% for hedging purposes. All figures based on 31 December, 2020.

But this does not explain why borrowers choose to, or are forced to, access private debt financing in the first place.

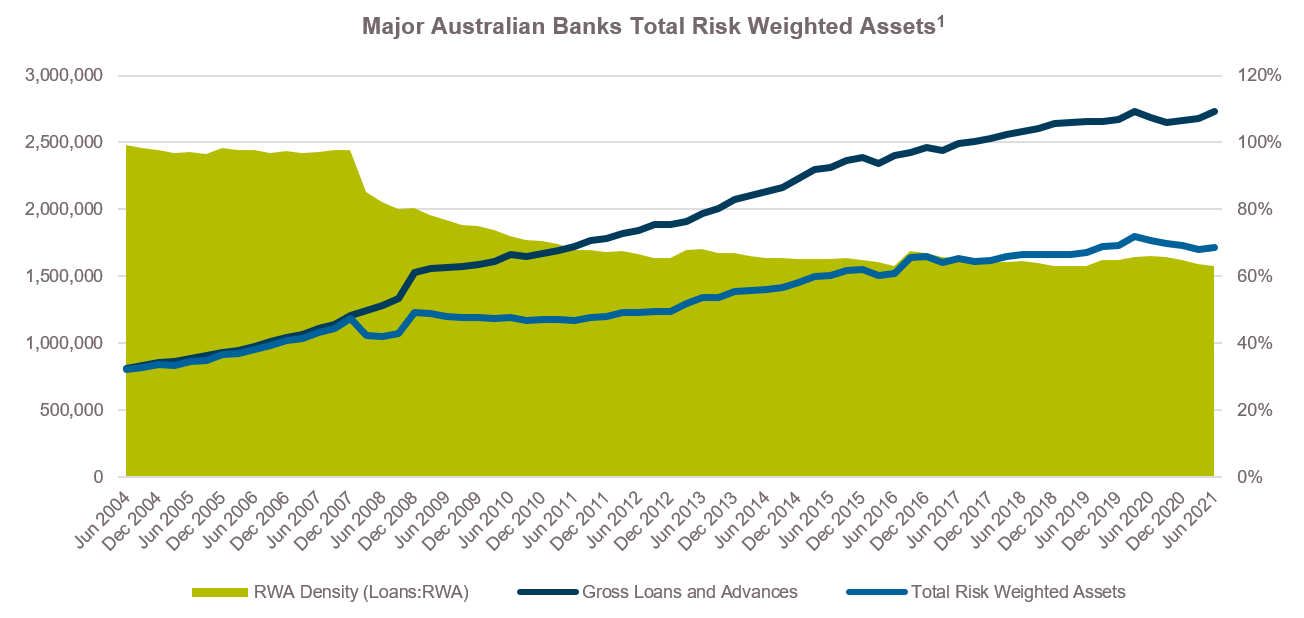

The Structural Decline in Bank Risk Appetite

Obviously a structural decline in bank lending to non-investment grade corporates, commercial real estate debt, non-public asset backed securities financing (such as warehouse funding facilities (2) for non-bank lenders), long-term project finance and other sub-asset classes of the private debt universe due to tighter regulatory and capital rules has decreased the options available to such borrowers. This increased cost to hold risk has meaningfully altered bank business models. As a result, banks have grown more conservative as they now must consider the risk-adjusted returns of potential loans in the context of more stringent and complex capital requirements – pushing them towards prime home loan origination at the expense of lending to businesses, for example.

Changes in bank lending patterns have an important implication for investors. Bank securities—both fixed income and equity—should have different risk-return profiles going forward, as investors in bank-issued bonds and stocks are much less exposed to mid-size corporate lending and many types of real estate financing as well as fixed income trading revenue via the balance-sheet activity of their bank holdings.

Source: 1 APRA, 2 Standard eligible mortgage with no mortgage insurance

While these regulations have made the global banking system safer and have reduced risk to the financial system, certain risk exposures have become prohibitively expensive for traditional banks as a result of the new rules, creating a funding gap that increasingly is being filled by non-bank market participants. These regulations also have ushered in the rise of ‘fintech’ lending platforms and financial-disintermediation technologies that provide individuals and small businesses access to new sources of financing. Private credit is often an important source of funding for such new business models, particularly via so called ‘warehouse funding’ prior to them being able to securitise assets into public markets.

But other factors play a role as well.

The Growth in Private Equity Sponsorship

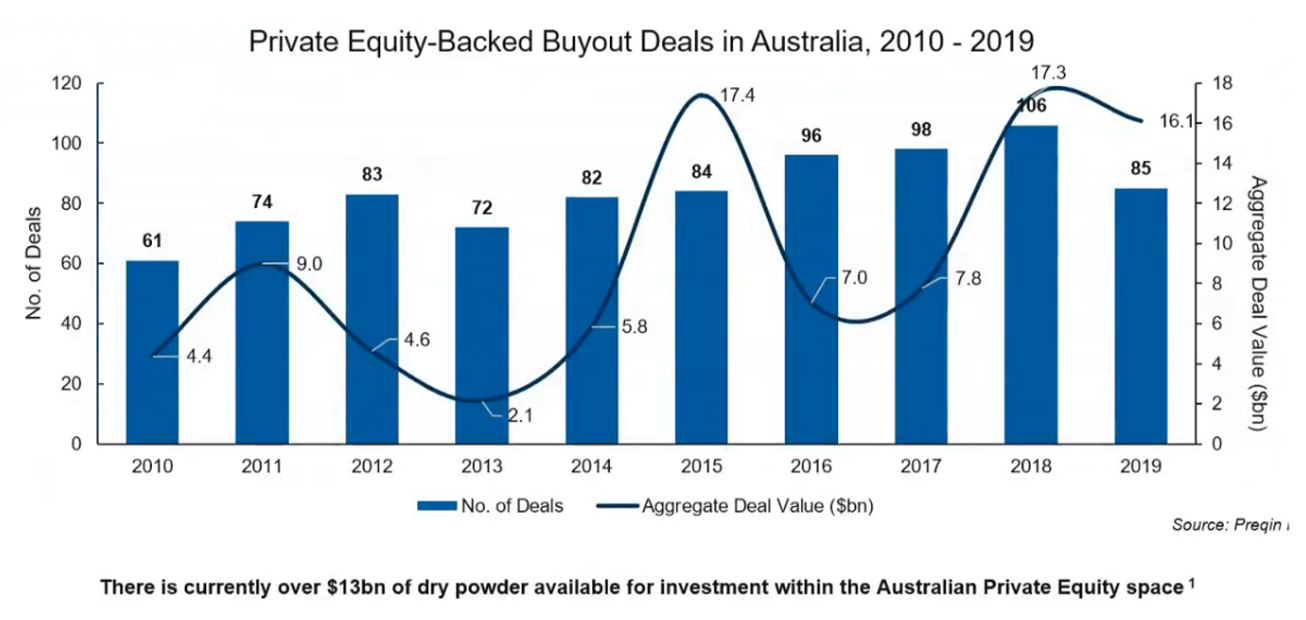

Firstly, the shift toward private markets has been a consistent macro trend over the past few decades: while private markets have grown substantially during this period, the number of publicly traded companies has declined over the past 20 years. As a result, there are more private companies that require debt financing to fund their growth. Therefore, making private loans to private-equity sponsor backed companies is a big source of private debt origination in Australia and offshore.

Generally, the private equity asset class has focused on companies with high cash-flow generation and stable business models, and the companies are often leaders in their specific segments.

Secondly, these borrowers are accessing private debt because they are looking for partners they can rely on to participate alongside them in a journey toward their objectives. They are also looking for some degree of flexibility or tailoring to line up the terms of their debt financing with their business objectives as well as speed and certainty of execution (particularly in a time-pressured acquisition financing scenario). Some or all of these factors are why many borrowers are willing to pay a premium over other lending alternatives.

Finally, many borrowers in private credit are too small to access liquid capital markets or don’t have the revenue and resources to justify paying for and supporting the due diligence of public credit ratings agencies like Fitch, Moody’s and S&P or covering the significant fees of an arranger (plus all the other service providers) who are tasked with structuring and distributing a debt package. Thus, private debt markets are an attractive source of funding for acquisitions, organic growth, and scaling through capital investment outside of raising additional equity.

In many ways, the making of a loan is analogous to the manufacturing of a product. In some cases it makes sense to have each stage of the manufacturing process (the due diligence, structuring, documentation and syndication) completed by a different party. But often it is more cost effective for a borrower to work with an individual lender who has internalised the manufacturing of a loan for themselves. What the borrower pays in terms of a higher interest rate is offset by the lower cost of the manufacturing process.

Source: Prequin Pro 2020, Australian Investment Council (AIC)

Lastly, an important distinction between public and private markets is that private lending markets are inefficient. In public markets, arrangers effectively run an auction process to establish the lowest yield at which they can sell all of the debt. In private markets, there is generally no auction process. Often a borrower will approach a very small number of lenders (in some cases only one lender, especially where there is a long-standing relationship) and consider the overall package- timeliness, flexibility of terms, execution risk (i.e. does the lender have to syndicate some risk in order to do the full deal), quality and reputation of the lender in addition to the cost of the borrowing. This inefficiency is an opportunity for private lenders, who arguably see more deals and have a better idea of risk and return than the borrower (or the borrower’s owner), to identify the best opportunities.

View Part Two here.

This piece was co-authored by Sam Morris, CFA – Senior Investment Specialist, Fidante Partners & Pete Robinson, Head of Investment Strategy and Portfolio Manager, CIP Asset Management.