This podcast was published on Livewire, 11 June 2024.

Note: This interview was taped on Friday, May 24 2024.

Given markets discounting a hard landing, it makes sense to prepare for the worst rather than hope for the best.

As a business owner and mortgage holder, I hope to see a few rate cuts from the RBA. I’m sure many people share those sentiments, with inflation pushing up the cost of living and also impacting business confidence.

In the same breath, however, I’m conscious that there’s a real chance that rates could go higher, elevated inflation may persist, and business conditions, whilst improving, may remain fragile. While I’m not excited about that scenario (my wife isn’t crazy about camping), I’ve planned for that possibility personally and professionally.

I have observed a more intense focus on RBA policy meetings this year than ever before. It’s almost as if the nation is collectively willing to get confirmation that we’re at the top, hoping that rates will start falling and providing some relief.

However, hope is not a strategy, and according to Coolabah Capital’s Christopher Joye, Challenger IM’s Pete Robinson, and Morgan Stanley Wealth Management’s Simon Mills, there’s a decent risk that the road ahead will have some big bumps.

Don’t be fooled by benign conditions

If you look across markets right now, multiple indicators suggest central banks have successfully orchestrated a soft landing – a feat so rare that it has only been achieved once before, back in the 1990s.

Equity markets have rallied strongly since October 2023, and even on a 12-month basis, you’re looking at 23% returns from a broad index like the S&P 500. That is slightly more than double the long-term average.

The VIX, a measure of expected volatility, is currently reading 13.11, which is close to 52-week lows and well below the 10-year average of 18.5.

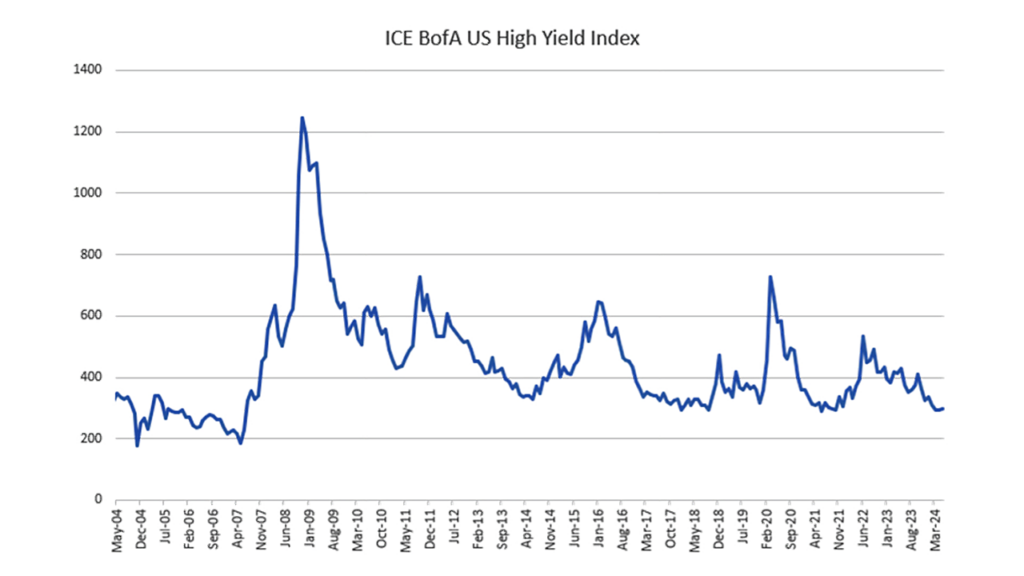

You can also look at US high-yield credit spreads, which have compressed to within 10 basis points of the post-COVID lows, which in turn are at their tightest levels in the post-GFC period.

So, what is the market missing?

According to Joye and Robinson, the soft-landing narrative is running on ‘hopium’ rather than reality, and the fight against service inflation has further to run.

Robinson, who traded US sub-prime credit for a London-based credit opportunities fund during the GFC, uses the analogy of “the pig and the python”.

“So the impact of higher interest rates has been delayed. It takes a long time to pass through the python. If you look at commercial property in the US during the GFC, it took three years for prices to bottom out,” he says.

Little transactional evidence has given investors a clear picture of valuations, and Robinson believes this is an essential detail in the current cycle.

Joye believes that central banks have far more work to do in the fight against inflation, which he describes as a ‘crisis’.

“We’re nowhere near landing on the price stability targets that central banks have, and we expect a hard landing. Right now, the world is characterised by an inflation crisis driven by demand side services inflation,” he says.

Joye argues that the only way to crush services inflation is to put downward pressure on wage growth by pushing up unemployment. Investors need only look across the ditch to New Zealand, where interest rates are 5.5%, to understand what that looks like.

“We think New Zealand is the canary in the coal mine. In New Zealand, they’re in a recession, they’ve had 12 months of negative GDP growth, and unemployment has increased from 3.2% to 4.3%,” he says.

Rate hikes are certainly not off the table and RBA Governor Michelle Bullock told a Senate estimates meeting that the RBA won’t hesitate in taking action if inflation remains sticky.

But it’s not all bad news

Despite the bearish tone, there is a positive underlying message for investors. Higher interest rates, a source of uncertainty, also offer a haven for investors to earn some income until better opportunities arise.

Morgan Stanley Wealth Management’s Simon Mills says there are structural tailwinds for private credit, and he is actively discussing this area with clients. Investors can receive a premium or extra return for investing in private markets, but that comes at the expense of daily liquidity.

“You can’t go and seek an illiquidity premium and then expect high levels of liquidity from that,” he explains.

Robinson and Joye share similar perspectives on the opportunities. For Joye, now is a time to stay liquid, floating rate, and in high-quality financials. Everything else, he argues, looks a bit rich.

Robinson spends most of his time in private markets, where he can take advantage of the illiquidity premium when public markets get expensive, like now. He also likes to keep the duration of his loans short to take advantage of the 90:10 rule.

“The 90:10 rule – 90% of the time, private markets offer that illiquidity premium when markets are generally stable. But there are these periods of volatility, and frankly, that’s when the best returns are available, and those returns are available in public markets, not private markets,” he explains.”