What We’re Watching: Lessons from the noughties: Fooling some of the people all of the time.

September 2024

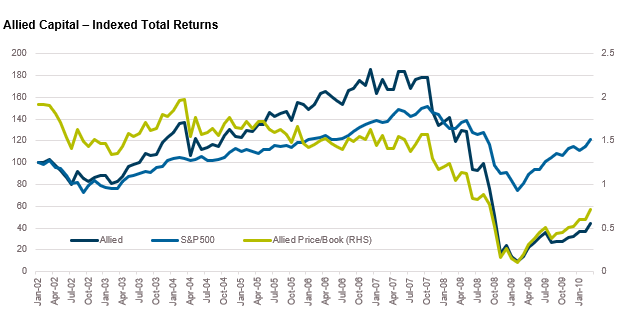

“Fooling some of the people all of the time” is a book written by hedge fund manager David Einhorn about a firm called Allied Capital, a US business development company focussed on providing mezzanine loans to private companies or commercial real estate assets. The book was based on Einhorn’s experience shorting the stock of the company which he believed had inflated the valuation of its illiquid securities and engaged in questionable accounting practices related to companies which they owned all or a substantial part of the equity. In June 2007, the Securities and Exchange Commission found that Allied had indeed broken securities law relating to its accounting and valuation practices. However Allied Capital’s valuation was remarkably resilient from 2002, the year Einhorn started shorting the stock, until mid-2007 when the Global Financial Crisis began. From mid-2007 until 2010, Allied Capital’s share price declined by 98% resulting in the sale of the company to Ares Capital Corporation in early 2010. Allied price to book ratio fell from around 1.5 times pre-GFC to 0.1 times at the lows as investors lost all confidence in the accuracy of the valuations of the underlying assets.

The book is a terrific read for those with a general interest in financial market psychology. Einhorn argued there were fundamental governance issues related to Allied Capital but for years the wider market did not seem to care.

Einhorn was not quiet in making his case either. He first talked about Allied Capital in 2002 at the famed Ira Sohn Conference. He published papers analysing Allied Capitals valuation techniques, wrote columns on TheStreet.com and even testified to Congress. But Allied continued to trade around 1.5 times book value. Many of the risks were known, (or should have been known) but investors underestimated their impact.

“So, what if they overvalued one or two loans. Not all loans could be misvalued.”

“So, what if there are conflict issues related to their owning equity and debt. That just gives them access to deal flow.”

The returns were too good. From the end of 2001 through the end of 2006 Allied Credit delivered a return of 10% per annum, over 3% per annum over the S&P500. The gross dividend yield was 8% per annum over that time.

It wasn’t until the GFC that investors accepted that poor governance could significantly exacerbate poor performance. Indeed, even as the share price declined to 10 cents, the book value of shares never declined below $6.65. The effect of the credit cycle was magnified when investors lost confidence in the underlying valuations. Ironically, the ultimate winner was another BDC, Ares Capital Corporation (ARCC) who acquired Allied Capital at a material discount to book value. Prior to the GFC, ARCC had never traded materially above book value and at the lows of the GFC maintained a price to book ratio north of 0.3 times. By the end of 2009, ARCC was again trading above book value. Today ARCC trades at a circa 1.1 multiple of book, has a market capitalisation of over US$13 billion and is part of the wider Ares Group which has close to US$450 billion in assets under management.

The point of this short history lesson is to remind us that governance might not matter too much in the good times. Poor valuation practices can be papered over by rising valuations. Conflicts of interest can actually be perceived in a positive light as lenders highlight better access to deals through their equity investments or vice versa. But when the cycle turns, poor governance can significantly exacerbate losses. Lack of trust can lead to outflows of capital which can result in further losses which if not appropriately valued can lead to further rude surprises for investments and further outflows of capital. Once trust is lost, the positive perception of related party transactions may turn negative leading to even more outflows and more losses.

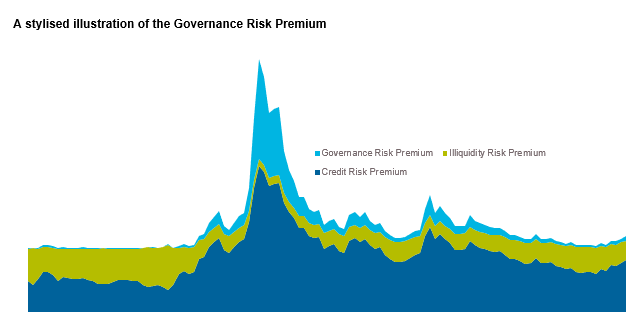

In private lending markets we talk a lot about illiquidity premiums which are the additional returns investors receive for investing in an illiquid investor which has similar credit risk to an illiquid investment. The reality is that there is also a governance risk premium which is positively correlated with credit spreads; ie the wider the credit risk premium, the wider the governance risk premium.

Over the past 12 months there have been countless articles on private credit and more recently many of them have discussed the need for better governance within the sector. Both ASIC and APRA have made separate statement expressing concerns regarding some of the practices in the private lending market including those which led to losses at Allied Capital during the Global Financial Crisis. Amber lights are flashing but losses have been muted so trust from investors remains high and governance risk premiums remain low. But for how long?

At CIM we share these concerns but don’t believe that the correct response is to avoid private lending. There are very valid reasons why private credit has grown as it has and structural factors which suggest that the excess returns available in private markets should persist. The real question is how to allocate to private credit whilst minimising the governance risk taken on. We’ll attempt to tackle this question in an upcoming webinar. Stay tuned.