What We’re Watching: Reading the fine print – February 2023

March 2023

Questions on valuation

The seemingly mundane topic of the valuation private assets is coming up more and more frequently these days. Thus far we have avoided it in our “What We’re Watching” pieces instead focussing on the more “interesting” topics of house prices, bank funding and the general outlook for rates.

But we are getting asked more and more about our thoughts on valuation and so this month we thought we would try to tackle this topic.

To begin with, let’s go back to first principles. There two approaches to valuing assets.1

- Historic cost accounting: this values an asset at the price paid for it at the time of acquisition less impairment

- Fair value accounting: this values an asset at the price it could be sold for in the open market

These starting principles for valuation apply for the valuation of all assets and liabilities.

Historically, the historic cost approach was preferred as it was less subject to manipulation. The argument for fair value accounting is that it makes information more relevant and timelier.

Each approach has its own merits and there is guidance from accounting standards boards around when to use fair value accounting and when to use historic cost accounting.

Within funds management, a fair value approach to valuation is the most common approach. In the United States the Investment Company Act of 1940 requires investment companies (“funds”) to use a fair value approach. Under Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) Standard 9 – Financial Instruments, financial assets may only be valued at amortised (i.e. historic) cost if the financial asset is held within a business model whose objective is to hold financial assets in order to collect contractual cash flows and the terms of the financial asset give rise on specified dates to cash flows that are solely payments of principal and interest on the principal amount outstanding.

So, the implications of this clause are that you can only use a historic cost approach if:

- You aren’t selling financial assets. If you sell financial assets, then you must fair value.

- You aren’t receiving variable/equity cash flows. If you own equities, then you must fair value.

So arguably some lending funds can use a historical cost approach to valuation, but most fund managers actively trade their portfolios to create value for clients and so must fair value. Further complicating this is the fact that regulatory bodies can effectively dictate certain approaches. APRA for instance, requires insurers and superannuation funds to use a fair value approach.

Banks tend to designate large parts of their lending portfolios as “hold to maturity” and thus hold them at amortised cost less provisions. They don’t intend to trade so this may appear to be a reasonable approach. However, the issues that have emerged at Silicon Valley Bank over the past couple of weeks highlight that intending not to trade may not be enough. Due to a sharp reduction in deposits the bank was effectively forced to reclassify the hold to maturity securities as they needed to sell them to repay depositors. Unfortunately, the market value of these securities was well below the amortised cost which effectively wiped out their capital base of the bank. On the flipside, Goldman Sachs was famed for preaching the risk management virtues of marking to market. During the GFC this provided early warning signs of a deterioration in the US subprime mortgage market which Goldman controversially hedged at the expense of its clients.2

Observation: Within funds management, a fair value approach is most common and most appropriate approach to valuation

While a fair value approach will generally be used within funds management, the real complexity comes in when you consider the different ways a fund can arrive at an estimate of the price an asset could be sold for in the open market.

APRA’s view, as stated in Prudential Practice Guide SPG 531 tries to establish a hierarchy for establishing fair value, which we have summarised below:

- If there are observable prices for that asset in the market, then that is the valuation used;

- failing this, if there are objective observable quoted prices for similar instruments in active markets, then these can be used;

- failing this, if there are quoted prices for identical or similar instruments in markets that are not active, then these can be used;

- failing this, market-based inputs, other than quoted prices, that are observable for the investments, the these can be used;

- Otherwise, subjective, unobservable inputs for investments where markets are not active.

Under the valuation hierarchy shown above, the first few below points correspond to fair value levels 1 or 2. Fair value level 3 refers to assets for which the fair valuation significantly depends on unobservable inputs. Funds are required to disclose the proportion of assets valued at each level of the hierarchy.

Within the private lending market, a level 3 input might be the illiquidity premium or the difference between the return on a public loan and a private loan of the same credit risk. Given the lack of a credit rating on the private side, the risk is effectively unobservable. For the vast majority of public assets there are observable prices of the same or comparable assets. These are level 2 assets. But private assets should generally be valued as level 3 assets. And this is where the next layer of uncertainty comes in.

Observation: there is uncertainty regarding whether private market valuations can be influenced by changes in public markets

The questions around fair valuation of private assets really come down to whether it is appropriate to ignore what is going on in public markets when setting valuations for private assets. APRA’s language above specifically refers to markets but without clarifying whether the market they are referring to is public or private.

There is relatively little guidance on this point, leaving significant discretion to fund managers and their investors to determine the valuation methodology they use. Within private debt markets in Australia, many appear to have elected to simply ignore public markets altogether and focus on private market valuations. This can result in them valuing the asset at the same level regardless of what the public market is saying. The end result being more or less the same as if the asset was valued at amortised cost. Many public debt managers would argue that the unitholders and fund managers are complicit here; both preferring the much lower volatility that comes with this approach.

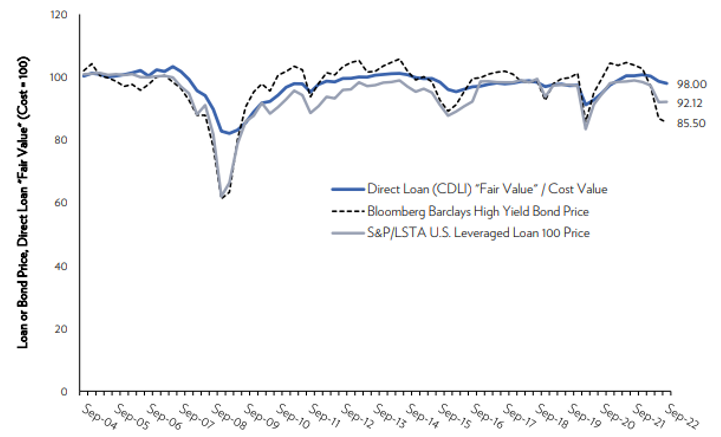

Unlike Australia, in the United States the valuation of private debt, while less volatile, certainly does appear to be influenced by public market valuations. This is shown below:

Chart: Cliffwater Comparison of Market Value versus Cost3

Valuation guidelines coming from Europe and the US are both a little unclear on what the input credit spread for valuation should be but do reference that public spreads should be a part of the consideration. The European Leveraged Finance Association suggests factoring in changes in observed spreads and yields of selected comparable debt indices (e.g. the Merrill Lynch High Yield bond Index and S&P LCD Loan Index, etc.).4

The upshot is that there is no set-in stone guidance which must be strictly adhered to but rather a series of principles through which investors can assess whether a fund manager’s approach is fit for purpose.

With this in mind, we have prepared a few practical questions which will help investors make this assessment.

| Question | Context |

| How do public market conditions factor into your valuation process? | To us, the argument that private market valuations are not impacted by public markets is a difficult one to hold. As investors, we adjust our required returns on new deals for prevailing market conditions. In April 2020, our required returns for new deals were a lot higher than they started the year. If returns in private markets didn’t adjust, we would simply deploy our capital in public markets until they did. If we are valuing new opportunities this way, we should value our back book in the same way. Of course, as the above chart illustrates, required returns for private deals may not respond to small changes in public markets. A 15 basis point move in public markets may not change our required returns, but a 150 basis point move would. |

| Who sits on your valuation committee? | The valuation committee should be independent to the portfolio manager of the strategy. APRA specifically called this out for superannuation funds, but it applies more broadly. There is a significant conflict of interest that comes from having investment personnel on the valuation committee. Investors should also know how frequently the committee meets, whether there is an audit trail and if there is an independent review of the valuation committee. |

| Do you trade loans in secondary markets? If so, how does this flow through to valuation? | Any transaction (buy or sale) should be considered as part of the valuation of the asset. Purchasing or selling an asset in secondary markets at a valuation that is materially different from the amortised cost also suggests that the fund is not in the business of holding assets to maturity. Fund financial reports should provide details of reclassifications from hold to maturity designations to available for sale. |

| How do you deal with a credit which is weakening? | This is an important issue, especially in the rising interest rate environment. Deterioration in credit fundamentals can be reflected through an adjustment to the expected cashflows or the discount rate, ideally both with the former for more severe deteriorations where loss of principal is likely and the latter for less severe deteriorations (say a downgrade from BBB to BB credit ratings). As a manager, we also want the ability to sell an asset that is underperforming if there is a better bid in the marketplace than the recovery value of the asset. This is not straightforward for assets held at amortised cost. |

| How do you communicate your valuation approach to clients? | If investors don’t understand how assets are being valued, then there is a risk of rude surprises upon any revaluation (i.e. investors having a different expectation of risk profile than the actual). Stable NAVs can lull investors into having a false sense of security. Transparency is key- valuation policies, with worked examples should be available to investors. Not properly communicating a valuation approach can significantly increase the risk of a run on the fund. |

| How are assets classified in the fair value hierarchy? | Understanding how an asset is classified within the fair valuation hierarchy can provide some insight as to how a portfolio is being valued. There will be fair greater valuation risk in a portfolio of level 3 exposures than level 2 exposures though investors should ensure that assets are properly categorised. |

| If assets are designated as hold to maturity, how can you be confident that you will not have to sell at some point in the future? | Being forced to re-classify assets from hold to maturity to available to for sale could cause significant changes in valuations. Thus, care must be taken to ensure that there is no risk that assets will be sold to meet a redemption. This means funds really need to have a redemption schedule that is longer than the maturity dates on the underlying portfolio. Silicon Valley Bank is the latest example of a bank that was forced to reclassify but private funds, particularly open ended ones, are equally as exposed. |

| How frequently do you revalue your portfolio? | From our perspective assets should be revalued any time money can go into or out of a fund. However even this may not be sufficient. Members of superannuation funds can switch options at no cost on a daily basis and so if they are invested in a private asset fund, they need to ensure that the fund NAV represents fair value on a daily basis. Under SPS 530 – Investment Governance, APRA has stipulated their expectation is that valuations should be conducted at least quarterly and consider triggers that would warrant a more frequent valuation. |

| What proportion of the portfolio has not had a change in valuation for 6 months/1 year/2 years? | Stale prices are fair value estimates based on information that is dated. There is a constant balance to be maintained between relevance (how comparable is the reference asset?) and timeliness (how recent was the observed trade?). High proportions of stale prices in a portfolio can be a tell that valuations are not being regularly or rigorously reviewed and leave a portfolio exposed to sudden and sharp changes in valuation if new information emerges. |

| How do you deal with upfront fees as part of the valuation process? | The treatment of upfront fees is an area of the market with little uniformity in approach. Under a historic cost approach, banks would typically collect the upfront fee5 and mark the asset at par less provisions. Under a fair value approach, the key question is if a buyer of the loan would consider the upfront fee as part of the overall economics of the loan. Our view (and the view of the global secondary loan markets) is that upfront fees are part of the overall economics of a transaction and so should factor in the valuation and not be retained by the manager. This being said there are circumstances where a loan may be revalued at a higher level reflecting a willingness from some investors to pay a higher price to access a deal that they would otherwise have missed. |

The recent run on Silicon Valley Bank and wider contagion risks are a stark reminder that a robust and conservative approach to valuation is critical. Not only does it reduce the existential risks relating to investors losing confidence in the governance of a business, but it also engenders discipline within the business as it forces management to address risks earlier and more transparently than otherwise would be the case. Lack of valuation discipline, particularly in floating rate credit can also result in inflated valuations and unitholders overpaying management fees.

Ironically over the past week it was actually Goldman Sachs, arguably the biggest cheerleader for the virtues of marking to market, that reportedly acquired a portfolio of underwater securities that crystallised a nearly US$2 billion loss at Silicon Valley Bank.6

Poetic justice indeed.

On behalf of the team thanks for reading.

Pete Robinson Head of Investment Strategy – Fixed Income

The information contained in this publication has been prepared solely for solely for the addressee. The information has been prepared on the basis that the Client is a wholesale client within the meaning of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), is general in nature and is not intended to constitute advice or a securities recommendation. It should be regarded as general information only rather than advice. Because of that, the Client should, before acting on any such information, consider its appropriateness, having regard to the Client’s objectives, financial situation and needs. Any information provided or conclusions made in this report, whether express or implied, do not take into account the investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs of the Client. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Neither Fidante Partners Limited ABN 94 002 895 592 AFSL 234 668 (Fidante) nor any other person guarantees the repayment of capital or any particular rate of return of the Client portfolio. Except to the extent prohibited by statute, Fidante or any director, officer, employee or agent of Fidante, do not accept any liability (whether in negligence or otherwise) for any errors or omissions contained in this report.

[1] We have tried to provide a summary of the thinking and background behind valuation methodologies. As the paper will show, it is a complex topic and often subject to much uncertainty. We are not accountants and welcome feedback as to where our interpretations of different standards and approaches are incorrect.[2] Goldman details their approach in this document: https://www.goldmansachs.com/media-relations/in-the-news/archive/risk-management-doc.pdf

[3] https://cliffwater.com/files/cdli/docs/Cliffwater_Report_on_US_DirectLending.pdf

[4] https://elfainvestors.com/publication/technical-guide-for-valuation-of-private-debt-investments/

[5] The treatment of upfront fees is a controversial topic itself with different views as to whether it should be considered a transaction fee and paid to the arranger of the loan (i.e. the investment manager) or considered part of the overall economics of the deal and paid to the lender (i.e. the unitholders of the fund).

[6] Reported by the Wall Street Journal, March 13.